Silent Film: Discover, Restore, Preserve then Show! (Part One)

TOP > 映画の復元と保存に関するワークショップ > Silent Film: Discover, Restore, Preserve, then Show! (Part One)

>> 日本語

Silent Film: Discover, Restore, Preserve, then Show! (Part One)

A Session from the 12th Film Restoration and Preservation Workshop

Silent Film: Discover, Restore, Preserve, then Show! (Part One)

Panels: Makoto Matsudo (Matsuda Film Productions), Hide Murakawa (Josai International University), Fumiko Tsuneishi (Filmarchiv Austria)

Mie Yanashita

One of the long time attendees of the workshop, Mie Yanashita, was a moderator for the first time in 2016, at a session titled “Silent Film is Alive – from an international point of view”, and she comprehensively introduced the popularity of Japanese silent films, the history of invited Japanese benshi performers such as Shunsui Matsuda, and present day benshi performances at festivals overseas to us.

This is the sequel of that session, titled “Silent Film: Discover, Restore, Preserve, then Show!”. We hope you all enjoy diverse episodes based on the rich experiences of Mie Yanashita herself and the three panelists.

Part One|Part Two

Yanashita: I’m Mie Yanashita, a silent film pianist. I’ve been attending this workshop from the first day, and because of such an intense program, I think you must be exhausted by now.

On the third day today, there are three sessions including this one, then feedback presentations about practical workshops or institutional visits on the first day, in addition to the “screening night” at Tokyo Laboratory’s theater nearby.

At least for this morning session, I hope you are able to sit back and relax.

Panelists (from right, Makoto Matsudo, Hide Murakawa, and Fumiko Tsuneishi)

I’ll introduce the three panelists.

First is Makoto Matsudo.

He is a grandson of the pioneer benshi performer Shunsui Matsuda I and son of Shunsui Matsuda II (1925-1987). As a managing director of Matsuda Productions, which has over 1,000 silent film titles in its collection, he is usually working behind the scenes, but I dragged him on stage today.

Second is a professor of Josai International University and a film critic, Hide Murakawa.

She is also known as the translator of Elia Kazan’s autobiography “A Life” published in Japan in 1999, or closer to this session’s theme, “A Passion for Films: Henri Langlois and the Cinematheque Francaise” by Richard Road, in 1985. She discovered the precious “Ukayama Collection”, which we will talk about later.

Thirdly is someone there is probably no need to introduce, but Fumiko Tsuneishi who gave us a keynote speech yesterday.

She was working as a film curator at National Film Center (NFC) from 2000, and in 2006 she started working at Filmarchiv Austria and is now the head of the technical department there.

“Fighting Friends – Japanese Style” discovered in the rice-producing region

Yanashita: This session’s title is “Silent Film: Discover, Restore, Preserve, then Show!” and first of all, I would like the panelists to talk about the discovery of long lost films, which is always dramatic.

In case of Prof. Murakawa, the trigger was the Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF), is that right?

Murakawa: TIFF used to be keen on showing Japanese classics and at the time we celebrated the centenary of cinema (in 1995), I was researching film director Mikio Naruse, and was very much looking forward to seeing Naruse’s works on new prints. *1

In the same year I got a call from my hometown, which is Shiozawa, Niigata, now called Minami-Uonuma city. As you know Minami-Uonuma is a snowy region and famous for producing Koshihikari rice.

According to my relatives, they tried to show Pathe-Baby (9.5mm) films as part of the celebration of the centenary of the town, but the old projector seemed to have been out of order, so they had no idea what to do.

I intuitively asked them to send me the list of the film titles they have.

The TIFF was going on at the time, so I looked at the list together with film critics such as Shigehiko Hasumi and Sadao Yamane (who were the programmers of the “Nippon Classics” at TIFF).

We were really surprised at the title “Fighting Friends – Japanese Style” (1929).

Yanashita: It’s the second oldest existing silent film by Yasujiro Ozu.

Murakawa: There was also Torajiro Saito’s “A Buddhist Mass for Goemon Ishikawa” (1930) and the discovery became big news in the media soon after.

The films’ owner was Mr Ukayama, a Shinto priest, and my family’s old friend. He was not a film collector, but came from a rich family, so to say “the landed class”.

He used to go shopping at department stores in Tokyo and one of his targets was Pathe-Baby.

Shiozawa is a historically lively area, and for the harvest festival in autumn, Mr Ukayama held film screenings in his shrine at night, which were very popular. I remember him as a very skillful, honest gentleman.

Yanashita: You’ve seen him?

Murakawa: When I was a kid, yes. Then I became a liaison between the Ukayama family and NFC.

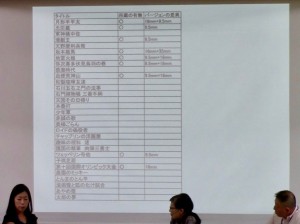

Yanashita: Here are 30 titles of the Ukayama Collection on the screen. What a wide range of genres! There are animations, too. Tomu Uchida’s “Return to Heaven” (1930) is also included.

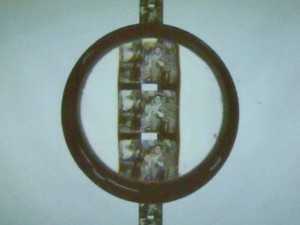

The restoration of the collection was led by Ms Tsuneishi at NFC, if I remember right, so I’d like you to talk a little about what 9.5mm films are.

Pathe-Baby/9.5mm film format

Tsuneishi: I started working at NFC right after the restoration of the Ukayama Collection and it was actually led by my ex-boss, Tomonori Saiki (head of the film section at the time).

Usually motion picture film has got perforations (sprocket holes) on the side(s), but 9.5mm has got them in the center, which means that the frame can be fully used from edge to edge, so the quality is almost as good as 16mm.

It’s an ingenious format, but you cannot fix both sides, so when it warped due to deterioration, you cannot achieve sharpness of the image. This is the burden of 9.5mm restoration. But the potential of one frame is extremely high.

It’s better for digitization, rather than film to film duplication, I think. The restoration is time consuming but worth the challenge, and I love this format.

By the way, I heard Prof. Murakawa’s story directly for the first time, so I’d love to know more details. Local people really used to enjoy “Fighting Friends – Japanese Style” at the festival site?

Murakawa: It’s a festival in the countryside, so samurai dramas were in demand, such as “Muttsuri Umon” (A hero from “Umon Torimonocho”).

If you take a close look at the samurai drama films, they are dirty and badly damaged, but modern dramas such as “Fighting Friends – Japanese Style” are in good condition, as they were not so often projected.

Tsuneishi: It seems to be true that Ozu films were not so popular.

Murakawa: I once did some research on film culture in my hometown, and found out that even after the war, Toho’s “Salaryman” series of comedies were not so popular. People definitely prefered Yakuza movies from Toei.

The reason why Mr Ukayama dared choose films not so much in demand is probably because he was from Ojiya High School in Niigata, which was known for its modern atmosphere.

Tsuneo Ikeda, the founding editor of “Baseball Magazine”, was also from the same school. Mr Ukayama must have been one of the “Modern Boys” in those days.

Yanashita: There is Hisatora Kumagai’s “Honruida (grand slam homer)” (1931) also in the Ukayama Collection.

Murakawa: Mr Ukayama loved anything new such as motor cars, musical instruments, and gramophone records. He picked up Pathe-Baby just because they were a novelty, then found out later that they were good in a real sense.

Tsuneishi: It was fortunate for us the projector was not working, and you got a call for help… if the projector had been working no problem then the films would never have shown up in front of us.

Murakawa: I pretty much think so.

Tsuneishi: At the time we got so excited at the discovery of the long lost Ozu film, but interestingly in the region, it was shown to the public, and it was not a secret at all that those films had survived through such a long time.

Locals never imagined that one of their nothing-special films was Ozu’s long lost title.

I don’t know the exact number, but probably a few hundred of each home use Pathe-Baby title from the product catalogue were sold, and “Fighting Friends – Japanese Style” from Ukayama Collection is one survivor.

Murakawa: There were two Pathe-Baby projectors in town.

Another one was at my grandmother’s house. Films found with it were documentary footage showing soldiers setting off for war or clearing snow. NHK archives would love them. But without any special knowledge, people don’t know what to do about them.

I heard from people at NFC that those long lost films were often discovered in film collectors’ houses, but there were no particular cinephiles in the region, and indeed I am researching films but it doesn’t mean that I’m familiar with film discovery or restoration work.

It was just a coincidence that happened during the TIFF and it brought the collection into the hands of professionals somehow.

Yanashita: The encounters or discoveries are always something like a series of coincidental happenings as if they have fallen down from the sky.

Discovery of long lost original negative of “Orochi”

Yanashita: Shunsui Matsuda II, Mr Matsudo’s father, must have been collecting films for business purposes, I suppose.

Comparing Matsuda Productions collection and the Ukayama collection, the following titles overlap, even though the format could be different.

Overlapping titles:

Tsukigata Hanpeita

Chushingura

Soteio

Sakamoto Ryoma

Jiraikagumi

Yaji and Kita: The Battle of Toba Fusumi

Chikemuri Kojinyama

Zeppelin go etc.

The 10th International Olympic Games

Matsudo: My grandfather was also a benshi, so my father started his career as a “child” benshi.

During wartime he joined something like a concert party, and after his return right after the war a fellow soldier asked my father to accompany him to Kyushu, where he was originally from.

“Since you were a benshi, a kind of entertainer, why don’t we set up a theater group?”.

Chikuho region, Kyushu in those days was in a coal-mining boom, so theatrical troupes were in demand, I guess.

Traveling as an actor, my father often had opportunities to bump into touring benshi with silent films, but I’ve no idea how they found such old films.

One day, he went to see one of those silent film screenings in a provincial area, which was exactly the same title he had seen in the village he stayed a few months earlier, and realized that a very important sequence was totally missing.

Even in their heyday, silent films seemed to have been shown like that, to make the total running time shorter. My father knew such a trick, so went up to the projection booth and complained,

“How dare you not show such an important sequence!”

The projectionist explained.

“I would love to if I could, but it’s a very old print you know, and badly damaged, so there’s no way to show it. I had to cut the part out and throw it away.

Being amazed that such a precious silent film survived through the wartime, however, the important sequence was THROWN AWAY!? My father was struck by the fact and asked himself.

“Hang on. Is the same film existing somewhere else or is this the last one remaining…?”

He restarted his career as a benshi later and I’m sure there were of course business reasons to collect old films, but the first step was this very moment when this feeling hit him.

Yanashita: I see… as a result of your father’s collection efforts, there are some titles only existing at Matsuda Productions and nowhere else in the world.

Among them, “Orochi” (1925) is especially popular. The first film after Tsumasaburo Bando, our movie star “Bantsuma”, started up his independent production company.

Matsudo: Indeed, “Orochi” is special.

The last movie theater my grandfather belonged to was the “Inohana-kan” in Chiba. As Bantsuma’s studio was also in Yaitsu in Chiba, my father appeared in some of their films as a child actor.

People would have thought that the son of a benshi could do acting easily.

In the studio, when one of Bantsuma’s apprentices Yojiro Bando gave training to young actors to act in sword fighting scenes, it seemed he often got frustrated and said,

“Give me a break… shame on your poor swordsmanship! I wish I could show you our master’s “Orochi”.

A climactic scene from “Orochi”(wikimedia)

“Orochi” was shot in the Taisho era, so my father had never seen it before, and he thought, “hmmm, there is such a big title”.

According to Yojiro Bando, it is a monumental film “so, stored at the master’s house for safety”.

For some reason my father became friends with Takahiro Tamura, and once asked him if the film still existed at home. But the answer was something like,

“There might have been films in a wooden box but when my father passed away (in 1953), it was a kind of panic in the house. I appreciated so many visitors came to mourn but after they left all the photos in our family albums had disappeared… after such chaos nothing film related was left for our family.

Yanashita: Even if you are not an expert of Japanese film history, you must know the Tamura brothers – Takahiro, Masakazu, and Ryo. Those famous actors are the three sons of Bantsuma.

Matsudo: Later on, my father heard a rumor that someone in Osaka owned the original negative of “Orochi” and visited the owner over and over again every time he went to Osaka to ask directly, “give it to me, please”.

The owner was ill and hospitalized but he was probably thinking of how he could make a fortune by showing “Orochi” when he recovered, so the offer was refused.

Time passed, and when he passed away, his family contacted my father to say,

“Well, we’ll give it to you as you were the most persistent one”.

Having obtained the negative, my father brought it to Buntaro Futagawa (1899-1966), the director of “Orochi”, who confirmed “this is it, exactly as I edited it”.

Yanashita: Wow…! The direcor was still alive! It was a very lucky example of discovery, I think.

Matsudo: The first screening event after the discovery was held in 1965.

The lack of a proper venue in the Tokyo area in those days was a problem, but suddenly the cancelation occurred at Kyoritsu Kodo in Chiyoda ward, capacity over 1,000, on the 7th July, and my father somehow booked it. *2

Yanashita: 7th of July is the traditional star festival day.

Matsudo: That’s the anniversary of Bantsuma’s death.

Yanashita: … how amazing!

Matsudo: Takahiro and Masakazu, Bantsuma’s sons, promised to join the screenings in Tokyo on the day after they held a memorial service on the anniversary of their father’s death in Kison’in temple in Kyoto.

My father did a big promotion for that, but tickets did not sell at all, so he did not expect too much.

Even so, it was a special screening after 40 years of the first release of “Orochi”. Eventually it turned out to be a full house and went successfully.

Present time movie stars such as Kinnosuke Nakamura were also in the audience. My father described it “as if Bantsuma called them”.

Yanashita: We are going to show an excerpt from “Orochi” with my live music. I’m not sure how lively it could be with this keyboard but please take a look at the famous sword fight at the climax of the film.

Live performance 1 – “Orochi” (Approx. three minutes)

Yanashita: I didn’t explain much about the story in advance but the main character played by Bantsuma who was tossed about by the fates was finally trapped in the end. A very powerful scene.

I recently played music for this “Orochi” in Ireland. There were people who had never seen Japanese silent films before but the audience all loved it and I got a standing ovation.

I confirmed this film was a masterpiece and its power was something universal.

Tsuneishi: I don’t know how many times I’ve seen “Orochi” but now I really would love to see the original negative. The story behind the discovery obsessed me right now.

Such fast cuts… only a few frames for one shot resulted in dazzling rapidity on screen, and each one of the cuts was spliced by hand!

Film director Daisuke Ito is also famous for sword fight editing.

According to his essay “Kurokoma kitan”, he inserted one or two black flames in the fighting scene to achieve so to say subliminal effects. But he mixed up negative and positive and it became white flame, which looked even more effective on the screen… I’ve learned about tremendous episodes from his essay.

In 2003 at the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, Japanese silents were featured, and the leading benshi performer Midori Sawato was invited to Italy and “Orochi” was shown thanks to Matsuda Productions with English subtitles, which was with not only the intertitles but also the whole lines of the benshi.

In additon to the power of the film itself, live benshi performance and music… that is the perfect match and nothing can beat it when you show Japanese silent films overseas. The excitement was outstanding.

>> Continued to Part Two

*1: “Nippon Cinema Classics” was one of the TIFF’s program series (1995-1998 and 2000-2008) and was a showcase of Japanese classics sometimes with new prints with English subtitles. Murakawa’s research on Naruse’s films was published in her 1997 book.

*2: It was called the pantheon of Japanese culture in those days, along with Hibiya Kokaido in Tokyo.

今後のイベント情報

- 12/03

- 動的映像アーキビスト協会(AMIA)会議

- 10/09

- 山形国際ドキュメンタリー映画祭 YIDFF 2025

- 09/08

- 保護中: FIAF倫理規定(改訂版 2025年4月)日本語訳

- 09/08

- 東南アジア太平洋地域視聴覚アーカイブ連合(SEAPAVAA)会議

- 08/16

- 紛争下の被災文化遺産と博物館の保護―スーダン共和国の事例から

映画保存の最新動向やコラムなど情報満載で

お届けする不定期発行メールマガジンです。

メールアドレス 登録はこちらから

関東圏を中心に無声映画上映カレンダーを時々更新しています。

こちらをご覧ください。