TOP > 映画保存とは > Choichi Imada, film technician

Choichi Imada, film technician

TOP > 映画保存とは > インタビュー / Interview > 映画フィルムの現像職人・今田長一

映画フィルムの現像職人・今田長一

>> 日本語

Although I don’t know if he knows the archivists’ slogan “Nitrate Won’t Wait”, Choichi Imada says, “Film-san is not kind enough to wait for us”.

I interviewed Mr Imada, a man with a career of more than 50 years in the field of film developing, at Ikueisha Co., located in Ekoda, Tokyo. They have always helped StickyFilms (former name of FPS). As you usually never have a chance to see films before restoration, only the result, it’s hard to imagine the difficulty of the process involved in striking a restored print. I hope I can show his passion for his job, saving the lives of so many dying films brought to the lab, and how much he loves films, through this interview.

1. The early years

Q: I’ve had some chances to talk to you before, but this time, I’d like to ask you some questions again in more detail. First of all, could you tell me how you got started in this film-related job?

Choichi Imada: I’m from Shimane prefecture. I came to Tokyo when I was 18 years old. There were no attractive jobs in such a remote countryside area. If there were any, they would be somewhere like a rice shop or barbers. Getting a job there doesn’t mean employment but apprenticeship. At first I tried to go to agricultural school, applied for it secretly and even got accepted, but I had to give up the idea because my family couldn’t afford the tuition. It was not the case in those days that you went to school and did some part time jobs at the same time, like students nowadays. I got to know about scholarships later, but it was too late, because I was making this application in secret, then I totally gave up. When I was 16 or 17 years old I was doing physical work carrying straw bags of rice to the rice vaults at an agricultural cooperative.

Choichi Imada: I’m from Shimane prefecture. I came to Tokyo when I was 18 years old. There were no attractive jobs in such a remote countryside area. If there were any, they would be somewhere like a rice shop or barbers. Getting a job there doesn’t mean employment but apprenticeship. At first I tried to go to agricultural school, applied for it secretly and even got accepted, but I had to give up the idea because my family couldn’t afford the tuition. It was not the case in those days that you went to school and did some part time jobs at the same time, like students nowadays. I got to know about scholarships later, but it was too late, because I was making this application in secret, then I totally gave up. When I was 16 or 17 years old I was doing physical work carrying straw bags of rice to the rice vaults at an agricultural cooperative.

The grandma of the current president of Ikueisha Co. (Kazuaki Miyamoto’s grandmother is the wife of the founder of Ikueisha, Kamenojo Miyamoto) was from my hometown. At the time, she informed us that the president she was married to was looking for somebody as an assistant, but I was the oldest son, so my dad said no, and my brother was born after my dad came back from the war, so he was still too young. I didn’t know much about motion pictures, however I’d been really interested in “film” for a long time, so I thought, “I really want to try!” and asked my dad. He said at last, “Go ahead, but only for three years”. That’s how I came out to Tokyo. Naturally I had to send money to my family otherwise they would not have been able to live on. Eventually, it became for good, not just for three years.

The grandma of the current president of Ikueisha Co. (Kazuaki Miyamoto’s grandmother is the wife of the founder of Ikueisha, Kamenojo Miyamoto) was from my hometown. At the time, she informed us that the president she was married to was looking for somebody as an assistant, but I was the oldest son, so my dad said no, and my brother was born after my dad came back from the war, so he was still too young. I didn’t know much about motion pictures, however I’d been really interested in “film” for a long time, so I thought, “I really want to try!” and asked my dad. He said at last, “Go ahead, but only for three years”. That’s how I came out to Tokyo. Naturally I had to send money to my family otherwise they would not have been able to live on. Eventually, it became for good, not just for three years.

You said you sneaked into the lectures at Nichidai (Nihon University, College of Art, Department of Cinema) and studied film developing. Was it around that time?

No. It was a little bit later on. Actually when I reached 20 years old, I met up by chance with a guy from my hometown in Ekoda. His father was a schoolteacher, and he was two years or so older than me. As I was gazing at his face, thinking he looked like someone I knew, he came to me and asked, “Good Lord! Are you Choichi-san?” That’s how we made friends with each other. I knew he was in Tokyo somewhere, but had not imagined at all he was in Ekoda. He was a student at Nichidai, so I got to know there was a cinema department for the first time.

At the same time, our business got busier and busier. In Nichidai or Waseda, there were so many students studying or shooting films. But if you think about Yokocine (now Yokocine D.I.A.) or Tokyo Lab in Chofu, they are really big in scale, aren’t they? Students cannot afford it. In those days there were a lot of small-scale labs all over the place, and Ikueisha happened to be close to Nichidai, so we had many students as our customers, and got along well with them. One of them, who got a job in a TV company and got promoted later on, was saying, “I want to learn about developing”, and we became close friends. When I said to him, “I want to go to the college sometimes”, as a joke he invited me saying, “You will get in OK as long as you’re with me. Why don’t you come?”. “Why not”, indeed. That’s how I sneaked into the campus, and went to classes to listen to the lectures. The professors probably knew that, or I don’t know but they didn’t say anything. Anyway, I was eager to learn, so I listened as hard as I could, so as to memorize everything they said. I had to find time to sneak out from my job for that, so the big man (Kamenojo Mori, the president) was angry with me and yelling like, “Where on earth were you? Did you go to the cinema or something?”

At the same time, our business got busier and busier. In Nichidai or Waseda, there were so many students studying or shooting films. But if you think about Yokocine (now Yokocine D.I.A.) or Tokyo Lab in Chofu, they are really big in scale, aren’t they? Students cannot afford it. In those days there were a lot of small-scale labs all over the place, and Ikueisha happened to be close to Nichidai, so we had many students as our customers, and got along well with them. One of them, who got a job in a TV company and got promoted later on, was saying, “I want to learn about developing”, and we became close friends. When I said to him, “I want to go to the college sometimes”, as a joke he invited me saying, “You will get in OK as long as you’re with me. Why don’t you come?”. “Why not”, indeed. That’s how I sneaked into the campus, and went to classes to listen to the lectures. The professors probably knew that, or I don’t know but they didn’t say anything. Anyway, I was eager to learn, so I listened as hard as I could, so as to memorize everything they said. I had to find time to sneak out from my job for that, so the big man (Kamenojo Mori, the president) was angry with me and yelling like, “Where on earth were you? Did you go to the cinema or something?”

Did you make good use of the things you learned at lectures?

That’s for sure. I learned everything about films, what “gamma” meant, and so on. Actually, in those days, there were no books. No single book about how to prepare developer. Probably because the used bookstore was near the college, I found a very difficult looking reference book about chemical analysis and I bought it anyway, but I didn’t understand a thing. By the way, it was still the black and white era. I didn’t know anything about color. I guess it existed somewhere in the world but up until the 1960s Ikueisha was far away from it. I got to know the difficulty of color when I did a job for Osamu Tezuka, for his TV animation. I had to think about color film that looks fine even in b&w. That was the time I realized how hard it was to work on color films.

Do you often go to movies?

Not at all recently, but well, there was a cinema called Ekoda Bunka when I was young, so I often went there. Now the building is used for a pachinko parlor, I wonder when the cinema was closed… when is the time cinema was told it was over? I graduated from a technical school in 1956, so…,

Did you go to school as well?

It was night school. To learn TV techniques, I went to school for two years. In those days I thought it was going to be the TV era. TV broadcasting started in 1948. To tell you the truth, I was told the president would let me go to school if I got to Tokyo, so I was really looking forward to it. I wanted to go to school, however it didn’t seem like it would happen, but I was not able to tell it directly to the boss. So I wrote a letter to a relative in my hometown to complain, and got told off. I guess it was grandma who said, “Do something for him”. I thought the night school at high school must be too hard, because, I actually started a correspondence course at Waseda – I was so ambitious, you know – but at the same time my job was busiest in the daytime. I had no time. My job finished at 12 midnight, and I had to wake up at six in the morning, so studying meant no sleep. It made me so dozy at work, the big man was furious, so in the end I gave up. But it lasted for about half a year. Still I couldn’t give up 100% about school, so I decided to go to technical school.

I know how you’re good at reconstructing machines and things.

I originally loved such things. I graduated, but… it was with the lowest results. The school was in Ikebukuro, so after school, when I got back to my job at 9:30 pm, others were still working. I also started work at night. In such a situation, how could I do homework? I had to take exams again and again. It was horrible. I stuffed my brain with answers for the exam. Sometimes visited my teacher’s place and asked about questions he was going to put in the exam. He was fed up with me.

Did you ask questions to the professors at Nichidai?

No way, ’cause if I did, they’d realize I sneaked in. Prof Yagi (Nobutada Yagi, who is the head of “Nihon University Center for Information Networking” and was presenter of the award Imada-san received from “Motion Picture and Television Engineering Society of Japan Inc.” in 1996), who is supposed to be quite high up now, his lectures were my favorite. But it was much later I had a chance to talk to him directly; when I was starting to get in the campus to be asked to repair or do maintenance of their facilities. At that time I said to him, “I already know your face!” I feel like now Nichidai is my home patch. I visit their developing area, borrow or lend machines or chemicals. And I know those professors very well, and we always say hello to each other. So now I’m OK. “Just borrowing something”, “Well OK then”, kind of relationship, really. Except for the entrance exam period, my face is my pass to get in. It’s much easier than before.

2. What he learned at the cinema

I’d like you to talk about cinema-going again. What kind of films did you prefer?

The film that struck the young me was Disney’s “Fantasia”. That use of frames. I don’t know how many times I went to see it. Many times anyway. In those days you could stay in the cinema as long as you wanted, so I was there all day long. When the water drops were falling, the scene was even more natural than reality, so I wanted to know how it could be possible, and watched it over and over again, without any luck. I’ve learned the most from that film technical-wise. I still think so. I didn’t get that strong emotion from Japanese films, not at all.

Is that because Japanese films were, in technical terms, always behind Hollywood?

That might be one of the reasons, but in those days, with sets or anything, the scale was much bigger in Hollywood, right? Japanese films looked smaller than foreign films if you saw them on the big screen. If you’re talking about stories, well, I remember Yasujiro Ozu’s “Early Summer”. I was a big fan of Chisyu Ryu, so at least I was watching Ozu’s films. And a few years ago, I forget the title but I saw a Toei film and was impressed how the technique had advanced. That’s all I can say about Japanese films.

I guess you are watching films in the theater, through your eye as a film technician, no?

I find a lot of flaws, that’s true. I probably have to watch it three times, but anyway, these days I’m trying not to watch them like that. The entertainment should be watched as an entertainment, I believe, without turning suspicious eyes on them. But when I was young, when I was still in my 30s or 40s, I was just watching films to find something negative. With a lot of suspicion.

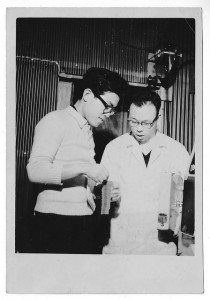

I wonder if there’re some, so to speak, students of yours, young staff working under your supervision, in Ikueisha?

Not so many, but some who have a projectionist’s background and wanted to learn lab work as well. I sometimes ask them to follow me all day long. Otherwise they are not able to learn.

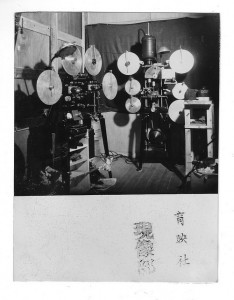

Ikueisha is not a big lab where people have their own role. You have to do everything by yourself. To learn so many different jobs in a short period of time, you have to be with me all the time. The films are from customers, so no mistakes are allowed. That’s why I teach them this old fashioned way. About the machine, the point is what you can do when something happens to it during operation, how to carry out maintenance work on it, and things like that. In addition, probably the most difficult work is repair, I suppose. Broken perfs, for example. Especially old films are trouble. How to make them able to go through the machine, which is the biggest problem. It takes quite a long time. Depending on the case but in the worst case, the really damaged ones, just one foot takes a few hours. I doubt many young people can handle that. Even me, it’s not easy after one hour or so. In that case, having so many different jobs is a good thing. If it’s a big lab, and I only do the dark room job for a day, I couldn’t stand it. I enjoy working here doing a lot of different things.

Ikueisha is not a big lab where people have their own role. You have to do everything by yourself. To learn so many different jobs in a short period of time, you have to be with me all the time. The films are from customers, so no mistakes are allowed. That’s why I teach them this old fashioned way. About the machine, the point is what you can do when something happens to it during operation, how to carry out maintenance work on it, and things like that. In addition, probably the most difficult work is repair, I suppose. Broken perfs, for example. Especially old films are trouble. How to make them able to go through the machine, which is the biggest problem. It takes quite a long time. Depending on the case but in the worst case, the really damaged ones, just one foot takes a few hours. I doubt many young people can handle that. Even me, it’s not easy after one hour or so. In that case, having so many different jobs is a good thing. If it’s a big lab, and I only do the dark room job for a day, I couldn’t stand it. I enjoy working here doing a lot of different things.

3. The shift to film preservation

When did you come across “restoration” in your career for the first time?

The beginning was when I struck a safety copy from the nitrate original of Emperor Hirohito’s visit to Europe, when he was still a prince (*This restoration was in 1972, from Tomijiro Komiya collection of National Film Center in Tokyo). I used a step printer and shot the frame one by one. It made me so sleepy and was really hard. Of course it was not the first time to deal with the old films but for me, it was the most impressive one. Even at that time, I had a mind to try and save the old films, not only new ones, and there was the reputation of Ikueisha “we can deal with any kind of films. If you have films with some complicated problem, take them to Ikueisha”.

That’s still the case even now, isn’t it? I guess when you tackle restoring such problematic films; you wouldn’t have enough time to finish it by the deadline.

People have to see it as soon as possible. That’s the hardest part of this business. At first they say, “I don’t care how long it takes” but in the end, they ask us, “Not ready yet!?” In such cases, whatever the result I have to finish it, even if it’s not a compromise, so I have no time for investigation or tests to my own satisfaction. But the films brought to us are, in most cases, already with no time to lose, so what can I say? We try our best to finish the job as fast as possible… there’s no choice. Then we have to keep going on.

Besides, I feel color restoration is the most difficult task. Color is depending on the people’s preferences, and it’s the projection that changes the look. It’s hard. Still now I’m struggling with tinted films. It’s impossible to make them look exactly the same as the originals. Just as close as the originals is the best I can do. However close to the color I got, for some people it’s nothing. Also, with early color films sometimes the balance is bad because of deterioration. I wonder if I should correct it or just leave it as it is. I sometimes think back on my lack of communication with the clients. I wish I had enough time for investigation. But I’m so proud of what I’ve done on black & white films. Our black & white is the best. That’s for sure.

Besides, I feel color restoration is the most difficult task. Color is depending on the people’s preferences, and it’s the projection that changes the look. It’s hard. Still now I’m struggling with tinted films. It’s impossible to make them look exactly the same as the originals. Just as close as the originals is the best I can do. However close to the color I got, for some people it’s nothing. Also, with early color films sometimes the balance is bad because of deterioration. I wonder if I should correct it or just leave it as it is. I sometimes think back on my lack of communication with the clients. I wish I had enough time for investigation. But I’m so proud of what I’ve done on black & white films. Our black & white is the best. That’s for sure.

Do you get some jobs from other labs?

Yes, indeed. The worst kind of deteriorated films. For example only the worst few rolls out of the 10 rolls of the work, not all of them. We cannot earn that much money out of them, and however good the result is, that’s not counted as our achievement, but we have to do it as long as we know that only we can do it. Later on the lab people ask me “How could it be possible for you to do that?”, then I answered such and such. They say, “That’s impossible! Whatever we tried, the film didn’t go through the machine.” I cannot stop laughing, like “if you can do it easily, I’ll be in trouble”. To make the impossible possible is Ikueisha’s skill. For film to film restoration, compared to film to video, the money you need is totally different. For ordinary people, film restoration is not an option. To make things much worse, if the film’s condition is bad, even if the client wishes to do film-to-film restoration, they usually give up, like “Is it that expensive!? Oh well I cannot afford it”. I don’t have the heart to leave the films I can possibly save in the lurch. I should do the best I can do. The former president was always saying, “Only this time, we accept this offer at the lowest possible rate.” Eventually, “only this time” repeats over and over again. But times have changed, like the case of digital restoration by foreign labs… I’m wondering and watching where the charm of films is going.

About digital restoration, I think it’s still in the experimental stage, even the work from foreign labs. I’m very interested in what a film expert like yourself thinks of their results.

To extract as much as possible of the real beauty of films, you cannot rely at all on digital technology, I think. Silver content is something altogether different. It’s film no doubt, projected, but there’s no depth of the gradation, as if you are watching it on video. There’s no sense of perspective, and the frame is frozen completely. I tend to think it was better to see shaky frames. But, if you really go down to digital, I hope all the scratches are gone, as it’s difficult without digital technology to erase scratches in the film-to-film restoration process. If it’s possible, that’s good. In my opinion, we enjoy beautiful images without scratches on video or DVD, and the films are just left with all the scratches. I mean, you can erase the scratches in the process of the telecine. And watch them on DVD, isn’t it enough? If you need to make a 35mm film from the digitally restored data,… I’ll try the blueish b&w not the brownish b&w. That technique is another story. Even if the digital restoration went well, if the film technique of the projection print is bad, it would be hopeless. Anyway, it’s the result the client judges, in other words, the people who pay the money decide what’s good or bad, so I’m not in the position to say anything. Only thing I can say is after several years, it’s definite some people start to complain about the digital techniques nowadays. They will realize the advantage of the silver image of the films. I believe so. Now you know that 8mm is booming again, especially among young people. Some TVCM directors say they shoot it on 8mm and telecine it, so the image has more perspective for some reason. That’s the kind of feelings that are already appearing.

For young people who know only the quality of video, probably the films’ look appears to be fresh, I guess?

I think they would say “Wow!” to it. It easier to shoot the same object and compare, but human beings’ memory is more than that. Somehow, in your eyes, digital images look flat and strange or not interesting… you get that impression. Even on TV, it happens. For example if you watch “Mito Komon” (*a very Japanese samurai era TV soap on the go for more than 30 years), it used to be shot on film but now it’s done on video, right? That’s so cheap looking, you can tell the difference immediately. I wonder at least whether they can do some tricks on it to make the look a bit better. But it’s difficult to explain how the difference appears in words.

I think some people don’t care at all about the difference, or some people would say the video production is more beautiful than the film….

Sure. I think the majority of people don’t care about it. That’s natural. No scratches, no dirt, that’s great! Here we go.

Are you doing restoration work right now? Have you come up with any new ideas and challenges? That’s the last question for now.

Recently, I don’t have much work on old films. The main work is 8mm, instead. I have no idea how long this 8mm boom will last, but about restoration work, I’ve learned a lot from experience and am always looking to achieve a better result than the last time. That’s my everyday task. There must be much better ways, I can improvise solutions very well… I always think that way. I’ve seen a variety of cases by now, so gradually I’m getting ideas, and can prepare the machine I need. Next time, I can try these new ideas, and get better results. That’s what I aim at. We cannot invest such a big budget like a big firm, so I’m sometimes jealous. But all I do is try my best with all my experience. I always do.

Thank you very much for today.

Please feel free to come back anytime, if this kind of talk is of any help, I can make time again.

October 20th, 2003 at IKUEISHA Co. Interviewer: K Ishihara

今後のイベント情報

- 04/08

- オーファンフィルム・シンポジウム

- 12/03

- 動的映像アーキビスト協会(AMIA)会議

- 10/09

- 山形国際ドキュメンタリー映画祭 YIDFF 2025

- 09/08

- 東南アジア太平洋地域視聴覚アーカイブ連合(SEAPAVAA)会議

- 04/28

- 国際フィルムアーカイブ連盟(FIAF)会議

映画保存の最新動向やコラムなど情報満載で

お届けする不定期発行メールマガジンです。

メールアドレス 登録はこちらから

関東圏を中心に無声映画上映カレンダーを時々更新しています。

こちらをご覧ください。