ライトニングトークの記録 2016 English

TOP > 映画の復元と保存に関するワークショップライトニングトークの記録 2016

On the second day of “The 11th Film Restoration and Preservation Workshop” in August 2016, the program included talk sessions of five to 10 minutes each by a total of 12 speakers covering a variety of topics. Celebrating UNESCO’s World Day for Audiovisual Heritage 2016, we translated four of them into English, hoping that their passion could be shared worldwide. We would like to thank all the speakers who attended, and also who gave us their kind permission to use those selected randomly below.

1.Reporting on George Eastman Museum 35mm Motion Picture Film Making

Emi Takano / IMAGICA WEST Corp.

Hello everyone, I’m Emi Takano, from IMAGICA WEST.

Hello everyone, I’m Emi Takano, from IMAGICA WEST.

I took part in a workshop held this June (in 2016) at George Eastman Museum in Rochester, NY, to make a 35mm black and white negative motion picture film.

>> Some photos from 35mm Motion Picture Film Making by courtesy of Joanne Bernardi

KODAK headquarters are in Rochester and the Kodak Tower is a symbol of the city. It was nice to find a window display at a craft beer place in the town decorated with Kodak film boxes or cameras.

Kodak succeeded in producing roll-film as a photochemical media for the first time in the world, which helped the birth of cinema by Thomas Edison or the Lumière brothers. The founder of Kodak, George Eastman’s house was renovated to be a museum. Their collections are cameras, history of photography and the Kodak company itself. There is a film archive as well.

This workshop consists of lectures, film making, film shooting, developing and scanning (digitization) all in four days and the attendees are limited to six in all. Actually three of them are in this venue today.*

*Other than Emi Takano, photographer Satoshi Chuma and Joanne Bernardi from Rochester University attended the 11th Film Restoration and Preservation Workshop.

Including making the emulsion as a photosensitive material, all the filmmaking process is basically conducted in the darkroom. The main substance of emulsion is gelatine. You add potassium bromide and silver nitrate to it and stir. After completion, you apply it on the base material. The base material is three times the width of a 35mm film, and rolled up. You cut this base about 12 feet long and apply emulsion on it, and cut it into three strips after drying. Then you crank the handle of the perforator to make perforations on both sides of the film.

Next stage is shooting outside with the film you made. You look at the light, judging if the background color is OK or not, for example if it is dark red, it becomes blacked out after the developing…… you think of such things all the way through, then change the shooting place and also consider the composition. The shooting time is about eight seconds for one film-strip of 12 feet long. Some volunteers like people who had retired from Kodak came to the museum and helped us by, for example, holding the reflector for shooting.

After the shooting we develop the film by hand and dry it to finish up. It takes half a day. The telecine (transfer to digital) is done by gathering together all six attendees’ negative films in one roll and scanning them together. Lastly, you get the part of the roll you shot and bring it home with you.

I’m thinking of doing this workhop in Japan someday. Please give me your support when the day comes.

Next 35mm Motion Picture Film Making Workshop will be before and after the Nitrate Picture Show which is going to be held from May 5th to 7th 2017 (before, the 1st to the 4th of May, and after, 8th to 11th of May, each can take a maximum of six people). The fee is US$900 plus $70 for materials. For more information, please contact at nitrate(a)eastman.org, George Eastman Museum

2. Small Gauge Film’s history and technology revealed by original objects

Sadanobu Iida

My name is Sadanobu Iida. I don’t belong to any academic societies or institutions, so have hardly ever had the chance to give a paper, but today, thanks to this opportunity I’m going to talk about my on-going study and research.

My name is Sadanobu Iida. I don’t belong to any academic societies or institutions, so have hardly ever had the chance to give a paper, but today, thanks to this opportunity I’m going to talk about my on-going study and research.

So far I’ve been doing research on small gauge films such as 16mm, 9.5mm, and 8mm, and I’ve been taking part in activities such as Home Movie Day (HMD) Yanesen as a projectionist, or as a former member of the Small Gauge Department of Film Preservation Society, which has now been partly taken over by Kogata-sha.

I published two reports in 2009. The first one is a basic reference for small gauge films shot in the prewar period, 1910s to 1940s, and the second one is to introduce Ichiro Kataoka’s 9.5mm film collection, including amateur filmmaker’s feature films or home movies.*

*Iida’s publications are available here (Japanese)

In addition, I took part in the research on the Takarazuka Revue film Haruno odori (Spring Dance) which is 16mm color footage shot by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, USSBS.

Let’s look at what kind of things I’m focusing on, which is really the equipment and the history of small gauge films. And I myself am collecting equipment such as cameras, projectors, editors, and I’m also into the film developing process, and collecting related materials as well as researching.

Through those real objects, there are things you can come to understand. Firstly, you can get the shift in technology by inspecting several objects at the same time (1). Secondly, sometimes if you compare written references and the real objects side by side, unknown facts are revealed (2). Thirdly, by examining the real things in so much detail, you can get the key to solve a long-time mystery (3).

I’ll tell you one of the examples of (1). If you take a look at Pathé Baby 9.5mm cameras manufactured in the 1920s from the very first hand-cranked model, you’ll see clearly that they gradually changed, as the following models were equipped with a clockwork motor, then afterwards the motor became a combined single unit with the main body.

An example of (2) is a piece of paper inside the old metal can for 16mm film. I had no idea what the paper was for or how to use it, but when I checked a reference book, it said to moisten this paper so that the film didn’t dry out in storage. So the mystery was solved.

There are also facts revealed by (3). For example, you can see these Kodak film paper boxes have handwritten numbers saying "18", and they are also stamped with the closer but not quite the same date "19th". I examined these numbered boxes carefully, and assumed that there was a scheme at the laboratory to control the films by these combined numbers.

There are also facts revealed by (3). For example, you can see these Kodak film paper boxes have handwritten numbers saying "18", and they are also stamped with the closer but not quite the same date "19th". I examined these numbered boxes carefully, and assumed that there was a scheme at the laboratory to control the films by these combined numbers.

While I was preparing this paper, I happened to obtain 29 reels of 9.5mm films together with a Pathé Baby projector made in the 1930s. So I’m thinking of researching these next. Just by taking a glance, I know they are all mostly short, about 10 meters each, home movies. I found a bag that also came with these films and according to it, the owner would probably have been from Osaka.

I’m planning to have an exhibition at Toy Film Museum in Kyoto in September 2016, and I’ll have a chance to give a lecture there, and also from November 1st to 6th, about 100 items of amateur film cameras and projectors from my collection are going to be exhibited in Jimbocho, on the second floor of Tokyo Kosho Kaikan (Tokyo Association of Dealers in Old Books). During this event, HMD Jimbocho will be held.

That’s all from me. Thank you for listening.

3. Introducing the research project on the cinema and music in the silent film era focusing on musical scores

Makiko Kamiya / Visiting Researcher, National Film Center, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (NFC), and Visiting Scholar, Waseda University’s Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum

I’m Makiko Kamiya. My talk today is a little different from the others and basically it’s about the “restoration” of the screenings’ style in the silent film era.

I’m Makiko Kamiya. My talk today is a little different from the others and basically it’s about the “restoration” of the screenings’ style in the silent film era.

This project started in 2014 and has been funded by the Collaborative Research Center for Theatre and Film Arts, Waseda University’s Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum (Enpaku). The project leader is Seiji Choki (The University of Tokyo), and the main members are Fumito Shirai, who studies Musicology (Research Associate at Enpaku), Kotaro Shibata (PhD candidate, The University of Tokyo), and myself as a film historian. Mie Yanashita (Silent Film Pianist) and Hidenori Okada (NFC) are also joining us to do research on the material belonging to Enpaku.

>> Mie Yanashita’s Bring a Piano to the Cinema!

The material we are working on is musical scores used by the musicians when they accompanied films for the movie theaters run by the film company Nikkatsu. There are nearly 800 items in total. This collection can be divided into published scores, handwritten scores, and scores distributed by Nikkatsu. As a distinguishing feature, there are more handwritten scores than published ones, and also, some scores distributed by Nikkatsu to the movie theaters they owned are included. At the mature stage of the silent film era, Nikkatsu was trying to control the musical environment in their theaters, and this collection is precious also in that it allows us to investigate the “distribution system” of scores by the film company in those days.

The scope of the collection is scores for silent films used in the middle of the 1920s up to the early 1930s. They were used in some Nikkatsu-owned movie theaters like Shinagawa Goraku-kan. As a result of the research, it seems they were actually used by a person called Hirano who probably worked as the musical master. The scores show the names of the Nikkatsu theaters such as Goraku-kan and Hirano’s name stamps on them. Thus we named this the “Hirano Collection”.

Not so much reference about Gorakukan remains, but we found an exterior photo in a local history book Medemiru Shinagawa-ku no 100 nen published by Kyodoshyuppanshya in 2001. The scores were used in this theater.

Not so much reference about Gorakukan remains, but we found an exterior photo in a local history book Medemiru Shinagawa-ku no 100 nen published by Kyodoshyuppanshya in 2001. The scores were used in this theater.

Hardly anything could be found on Hirano himself, but luckily we found his name in the list of musicians in Japanese film’s yearbook, Nihon Eiga Nenkan published in 1925. According to this, he was a pianist at a movie theater called Kanagawa Engei-kan around 1924 to 1925.

Our purpose is to explain the musical accompaniment in the silent era movie theaters by analyzing the Hirano Collection, and restore the screenings with live music in those days. The Hirano collection has scores with film titles, meaning that they are scores composed for or arranged for the particular film. We chose some of those scores to try to recreate screenings in the past. For example, we screened Gunshin Tachibana chusa (Lieutenant-Colonel Tachibana), directed by Genjiro Saegusa in 1926, with benshi performer Ichiro Kataoka and music by “Colored Monotone” at the Ono Auditorium, Waseda University in September 2015. Also in January 2016, we screened Yarikuyo directed by Kichiro Tsuji in 1927 with Mie Yanashita’s live piano accompaniment also at the Ono Auditorium, and we asked Ichiro Kataoka again to perform for Chushingura directed by Tomiyasu Ikeda in 1926.

Chushingura had just been newly discovered after being long lost, and was kindly offered to us by Toy Film Museum, Kyoto.

I’ve really run through all of this very quickly, but you can read it in detail in Enpaku’s journal Engeki kenkyu No 39 in 2016, which is on their website (in Japanese). We are planning to continue researching the Hirano Collection, and will do our best to show it on film, which we haven’t been able to accomplish to date because of the budget and venue’s limitation.

>> Engeki kenkyu

That’s all and thank you so much.

This talk is based on the results of research funded by the Collaborative Research Center for Theatre and Film Arts, Waseda Universitybs Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum (Enpaku) under the auspices of the Joint Usage/Research Center of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Research on silent film era screenings, especially about the material related to musical scores, took place in 2014-2015, and on silent era movie theaters and music, focusing on musical scores, in 2016. The “Hirano-Collection” belongs to Enpaku.

4. Live Skype from the International Silent Film Festival Manila 2016

Hidenori Okada / National Film Center, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

Hello. It’s rainy season here in Manila so we have heavy squalls from time to time. And also heavy traffic jams prevent us from getting around smoothly in the city, but the festival itself is going OK.

Hello. It’s rainy season here in Manila so we have heavy squalls from time to time. And also heavy traffic jams prevent us from getting around smoothly in the city, but the festival itself is going OK.

First of all, Ibll talk about what kind of film festival I’m attending here. Actually I wanted to skype from the festival live from the venue, but they didn’t have wifi so now I’m at my room in the hotel.

If you are familiar with this area of research, I mean, silent films, you may think of Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone, Italy or Bonner Sommerkino in Bonn, Germany, however the festival sites are really expanding. For example, the Silent Film Festival in Thailand celebrated its third year this year (2016), and the International Silent Film Festival Manila started from 2007 and this is its 10th year. I myself have been involved in the selection of Japanese silent films for this festival since the 7th year in 2013.

There’s no office or secretariat for this festival, but each country’s cultural organization based in Manila is gathering to have meetings and they offer one silent film per country to form this festival. Starting from three countries, this year there are nine in all, meaning six European countries, the US, Japan and the Philippines. So nine silent films are being screened.

It doesn’t mean that this festival is categorized with the same sort of concept as those western silent film festivals. What makes this festival unique is that the live music is performed by local musicians, and the genres are Rock’n'Roll, Pop, or Jazz, though live piano performance are common in Japan or western countries for silent films. And for the publicity, they put the same emphasis on those musicians as on the film titles.

The venue for the festival is a screen in a multiplex in a shopping mall. The capacity seems to be about 350 seats. I was very surprised talking to the locals to know that so many young people who are especially into art are attending. And all screenings are free of charge. No wonder that some of them are motivated to come for those famous musicians’ performances. In a way, I suspect it’s a new type of film festival.

I should mention the local silent films since I’m here in Manila. The leading film historian in the Philippines, Nick Deocampo, is writing that the first person to shoot a film in the Philippines was American, and it was in 1912, and the first film shot by a native Filipino was in 1919. If you think about the year 1919 in Japan, film production had already started, and it was when the Pure Film Movement had just begun, to advocate a more modern style of filmmaking over the old style. The first Philippine film was shot at such a time.

The Philippine silent film was screened yesterday. The title was Maicling pelicula nañg ysañg Indio Nacional (A Short Film About the Indio Nacional) directed by Raya Martin in 2005. It is 96 minutes long, so not necessarily short, but this was shot on black and white film with standard aspect ratio. 80% of the total was silent, and in the silent footage you’ll see intertitles. A Rock’n'Roll band accompanied it. “Indio national” means people who lived before the Spanish invasion. After over 300 years of Spanish rule, the US occupation lasted about 50 years, and after three years of Japanese invasion, the Philippines finally gained its independence. This film depicted the severe history as an allegory, so to say, by imagining what kind of works would have been created by native Philippine people if they had the tools like film making on their own…… I felt like the director thought highly of showing such a situation.

The Philippine silent film was screened yesterday. The title was Maicling pelicula nañg ysañg Indio Nacional (A Short Film About the Indio Nacional) directed by Raya Martin in 2005. It is 96 minutes long, so not necessarily short, but this was shot on black and white film with standard aspect ratio. 80% of the total was silent, and in the silent footage you’ll see intertitles. A Rock’n'Roll band accompanied it. “Indio national” means people who lived before the Spanish invasion. After over 300 years of Spanish rule, the US occupation lasted about 50 years, and after three years of Japanese invasion, the Philippines finally gained its independence. This film depicted the severe history as an allegory, so to say, by imagining what kind of works would have been created by native Philippine people if they had the tools like film making on their own…… I felt like the director thought highly of showing such a situation.

He was 21 years old when this film was made, and it looked a little rough but I think he was kind of very brave, and I received the power of modern Philippine films from it.

You can see silent films just esthetically or in so many other ways, but at least this time, I learned a wider perspective by seeing what kind of existence silent films could get in a former colonized country, where no domestic early films existed.

Another film shown yesterday was an Italian film titled Maciste All’ Inferno (1925) directed by Guido Brignone. The character Maciste is a Hercules-like figure often used in early Italian films, and Deocampo did an introduction for this film. He is researching so many aspects of Philippine film history but the most important theme these days is the perception of early Italian film in the Philippines. For example, the record of screenings of Giovanni Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914), or how those actresses, such as Francesca Bertini or Pina Menichelli, were perceived in the Philippines. I notice that such a stimulating, brand new area of research is emerging right now.

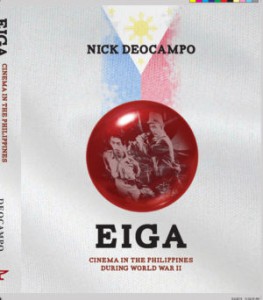

Deocampo also published a book recently titled Eiga which is about Philippine films under Japanese occupation.

Deocampo also published a book recently titled Eiga which is about Philippine films under Japanese occupation.

I just finished a talk session with him today. As the venue is a multiplex in a shopping mall, our talk on silent films was set in a large open space, like an atrium style, which was also quite a fun experience. I understood that the shopping mall and multiplex are both very cooperative and supportive for realizing this kind of event.

There is a leaflet for this festival but no official website. It seems young people in the Philippines prefer facebook pages, and the equivalent of an official website is this festival’s facebook account.

Today we will show Minoru Murata’s Muteki (The Foghorn) in 1934. I’m also looking forward to seeing people from film archives here. As you know the Philippines is such a huge film producing country but the public film archive was founded not so long ago.

That’s all from me. Thank you so much.

今後のイベント情報

- 12/03

- 動的映像アーキビスト協会(AMIA)会議

- 10/09

- 山形国際ドキュメンタリー映画祭 YIDFF 2025

- 09/08

- 保護中: FIAF倫理規定(改訂版 2025年4月)日本語訳

- 09/08

- 東南アジア太平洋地域視聴覚アーカイブ連合(SEAPAVAA)会議

- 08/16

- 紛争下の被災文化遺産と博物館の保護―スーダン共和国の事例から

映画保存の最新動向やコラムなど情報満載で

お届けする不定期発行メールマガジンです。

メールアドレス 登録はこちらから

関東圏を中心に無声映画上映カレンダーを時々更新しています。

こちらをご覧ください。